How Firms can manage New Ventures as Extensions of their Advanced Product Development

New Ventures have Collectively Become Every Corporation’s Research Lab

Ikhlaq Sidhu, UC Berkeley

Evangelos Simoudis, Synapse Partners

The World of Innovation Has Changed

A great deal has changed in corporate innovation since the days of Bell Labs and Xerox PARC. While these models of advanced work led to so many innovations and created tremendous economic value, it’s clear that large scale, insulated corporate research is no longer the most common model for entering new markets or developing technologies of the future. Even Google X is reevaluating.

What has changed? For most companies, open innovation and start-up acquisitions have become extensions of the firm’s advanced R&D portfolio. At the same time entrepreneurs and their investors have become much more effective and skilled at efficiently creating new innovations. And finally, a significant fraction of University lab work has now evolved from the traditional “publish or perish” model to one that is today closer to demonstration, design-oriented, and more applied than ever before.

All of these changes are about to converge into a new model for creating and managing portfolios of innovation.

From a Company’s Viewpoint, Some Problems Remain

The result today is that companies are now more symbiotic with new ventures and university research projects than ever before, however some significant barriers still exist. So many firms now have a Corporate Venture arm and/or Innovation Outpost in Silicon Valley. And in fact, Innovation Theater has even become rampant, which is the idea of mimicking innovative firms with dress or hairstyle but without actual technical or entrepreneurial substance.

This context illustrates the situation for many these groups assigned to a corporate innovation function:

- Many groups believe that they just need to find a magic technology that they can bring into their firms.

- They spend lots of time looking at new ventures and university projects in order to report what is happening back to a parent organization or parallel organization, which is largely consumed with other issues, like keeping the main business running and satisfying their existing customers.

- A very significant amount of time goes into communicating back and forth between the innovation focused groups and the main business units, but most proposals for acquiring innovation are not executed. In this case, we are not talking about acquisitions for market share, but instead for new markets or new technologies.

- When acquisitions happen, particularly too early, the firm ends up killing the new venture.

- Conversely, when the firm delays too long, it becomes prohibitively too expensive.

- There is a lot of “early stage confusion” on the topic of “why are we doing this”? Is this R&D, is it a future business unit, is it a marketing function to show we are leaders to our customers, and how do you justify the time that we are spending on this?

- This leads to the classic “Air Sandwich” in the organization. The top leadership loves what it sees in terms of demos, visions, and plans. The people focused on new innovations have great skill and are working hard. And yet, there is no momentum in the middle.

The Problem in more detail: No Portfolio Management

The reason it is so hard is that every idea is being managed on a case-by-case basis. There is no concept of portfolio. And further, there is no mapping between the internal portfolio of projects and the external portfolio of ventures and technologies.

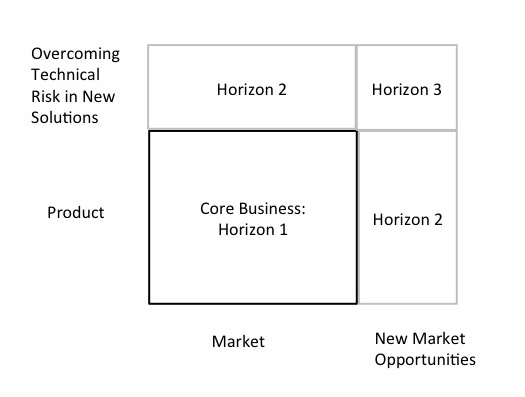

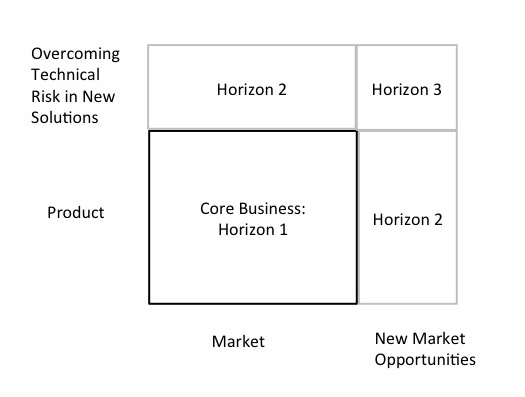

Consider this clarifying and well-accepted model below. When acquisitions are for market share, they exist in the core business (Horizon 1). There are always new initiative at every firm that test new markets and new product innovations (Horizon 2) and that the firm must learn in these new areas to stay successful. Horizon 3 refers to the case when a firm must learn both a new technology and new market.

But Here is a New Idea

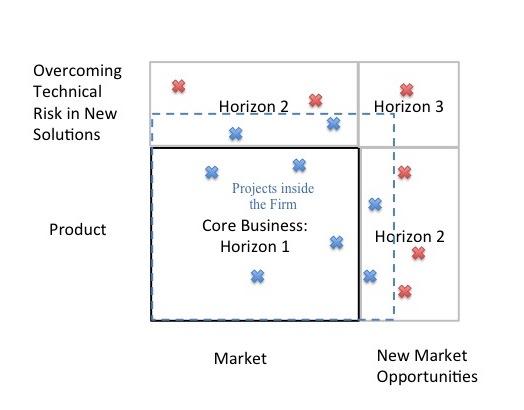

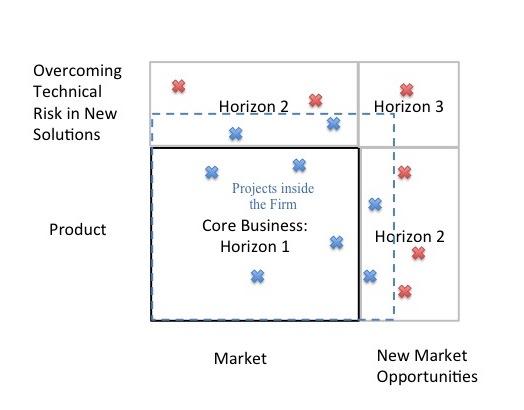

Now consider that some experiments in Horizon 2 and 3 are actually not within the walls of the firm but they are new ventures and/or technical projects in universities. In this case shown below, the Blue X symbols represent projects inside the firm, where Red X symbols represent new ventures outside the firm. First, projects outside the firm can be considered extensions of the internal advanced R&D and business creation process. And second, when mapped in this way, all the projects together make a portfolio, which can be financially managed like any other portfolio.

A simple but important point, all of these projects need both communication and relationship management, and not only to be tracked within a list. As projects become more relevant to any given company, the engagement must change from awareness, to board positions and strategic investments, partnerships, supplier agreements, and hopefully acquisitions. These stages must also be managed strategically with an understanding of timing in the relationship as well as strategic understanding of what the new venture can do for the firm.

Over time, some of these projects (external and/or internal) fail and must be removed from the respective portfolio, while others emerge as promising new businesses and become candidates to transition from Horizon 3 and Horizon 2. They are on their way to eventually become the corporation’s next-generation business units in Horizon 1. During this transition, the new businesses should receive additional resources from the corporation and their staff be augmented with individuals, particularly executives, who know how to start scaling businesses.

Is this a new idea? Not completely. Most firms do some variation of this already. Many business unit size acquisitions start out as friendly relationships while the new firm is much younger and the relationship is cultivated over time. The new idea here is that it can be done systematically and strategically within a portfolio instead of as random events.

The Step-by-Step Solution

So what does all this mean for your firm. Here are the simple steps.

- Make a list of your internal projects.

- Make a list of the start-ups you are watching. If you are not watching any, you might want to rethink your approach.

- Unroll the portfolio diagram above. Here is an example

Of course, spreadsheets work pretty well for detailed portfolio tracking. Many firms will do it differently based on their industry types. However, to get started and make this practical, consider column headings such as firm name, stage in portfolio, insights learned per firm, engagement priority, engagement or dis-engagement decision, and of course the changing context and arguments of strategic fit.

In Summary

Large firms and small firm and even university projects are symbiotic, but there are natural barriers that keep them from working together. While this is a larger issue to solve with education and research, for action-oriented firms, the issues are really more about timing, building relationship, and overall portfolio based tracking.

Our position is that it is time to step away from future stories about how the world will change and re-introduce some basic portfolio tracking methods into the innovation process. Of course, it is still crucially important for each firm to know what its future story and strategy will be in order to make sense of its own portfolio. But, the good news is that this problem that is tractable to solve. With an approach to innovation of this type, there will be less reliance on explaining how “deep learning” or “virtual reality” works and more on how the spreadsheet works, and finally your CFO will understand what you are actually talking about.

Viewpoint Highlight:

“From a start-up standpoint, the most common problem I see is potential acquirers – all those big, synergistic companies – not having a clear picture of what’s of strategic value to them. What’s needed is a simple way for these large organizations to map their existing assets, their assets under development, and those small, acquirable companies who provide complementary value to the business.” — Partner, Silicon Valley Venture Fund

“Most acquisitions at Google have had previous relationships develop between people for a long time, even though these firms typically don’t have business relationships with Google during that time. Its seems like they just happen quickly, but actually the relationships have taken time to develop” — Google Executive

Cross-link with Re-Imagining Corporate Innovation with a Silicon Valley Perspective, Evangelos Simoudis

How Firms can manage New Ventures as Extensions of their Advanced Product Development

New Ventures have Collectively Become Every Corporation’s Research Lab

Ikhlaq Sidhu, UC Berkeley

Evangelos Simoudis, Synapse Partners

The World of Innovation Has Changed

A great deal has changed in corporate innovation since the days of Bell Labs and Xerox PARC. While these models of advanced work led to so many innovations and created tremendous economic value, it’s clear that large scale, insulated corporate research is no longer the most common model for entering new markets or developing technologies of the future. Even Google X is reevaluating.

What has changed? For most companies, open innovation and start-up acquisitions have become extensions of the firm’s advanced R&D portfolio. At the same time entrepreneurs and their investors have become much more effective and skilled at efficiently creating new innovations. And finally, a significant fraction of University lab work has now evolved from the traditional “publish or perish” model to one that is today closer to demonstration, design-oriented, and more applied than ever before.

All of these changes are about to converge into a new model for creating and managing portfolios of innovation.

From a Company’s Viewpoint, Some Problems Remain

The result today is that companies are now more symbiotic with new ventures and university research projects than ever before, however some significant barriers still exist. So many firms now have a Corporate Venture arm and/or Innovation Outpost in Silicon Valley. And in fact, Innovation Theater has even become rampant, which is the idea of mimicking innovative firms with dress or hairstyle but without actual technical or entrepreneurial substance.

This context illustrates the situation for many these groups assigned to a corporate innovation function:

- Many groups believe that they just need to find a magic technology that they can bring into their firms.

- They spend lots of time looking at new ventures and university projects in order to report what is happening back to a parent organization or parallel organization, which is largely consumed with other issues, like keeping the main business running and satisfying their existing customers.

- A very significant amount of time goes into communicating back and forth between the innovation focused groups and the main business units, but most proposals for acquiring innovation are not executed. In this case, we are not talking about acquisitions for market share, but instead for new markets or new technologies.

- When acquisitions happen, particularly too early, the firm ends up killing the new venture.

- Conversely, when the firm delays too long, it becomes prohibitively too expensive.

- There is a lot of “early stage confusion” on the topic of “why are we doing this”? Is this R&D, is it a future business unit, is it a marketing function to show we are leaders to our customers, and how do you justify the time that we are spending on this?

- This leads to the classic “Air Sandwich” in the organization. The top leadership loves what it sees in terms of demos, visions, and plans. The people focused on new innovations have great skill and are working hard. And yet, there is no momentum in the middle.

The Problem in more detail: No Portfolio Management

The reason it is so hard is that every idea is being managed on a case-by-case basis. There is no concept of portfolio. And further, there is no mapping between the internal portfolio of projects and the external portfolio of ventures and technologies.

Consider this clarifying and well-accepted model below. When acquisitions are for market share, they exist in the core business (Horizon 1). There are always new initiative at every firm that test new markets and new product innovations (Horizon 2) and that the firm must learn in these new areas to stay successful. Horizon 3 refers to the case when a firm must learn both a new technology and new market.

But Here is a New Idea

Now consider that some experiments in Horizon 2 and 3 are actually not within the walls of the firm but they are new ventures and/or technical projects in universities. In this case shown below, the Blue X symbols represent projects inside the firm, where Red X symbols represent new ventures outside the firm. First, projects outside the firm can be considered extensions of the internal advanced R&D and business creation process. And second, when mapped in this way, all the projects together make a portfolio, which can be financially managed like any other portfolio.

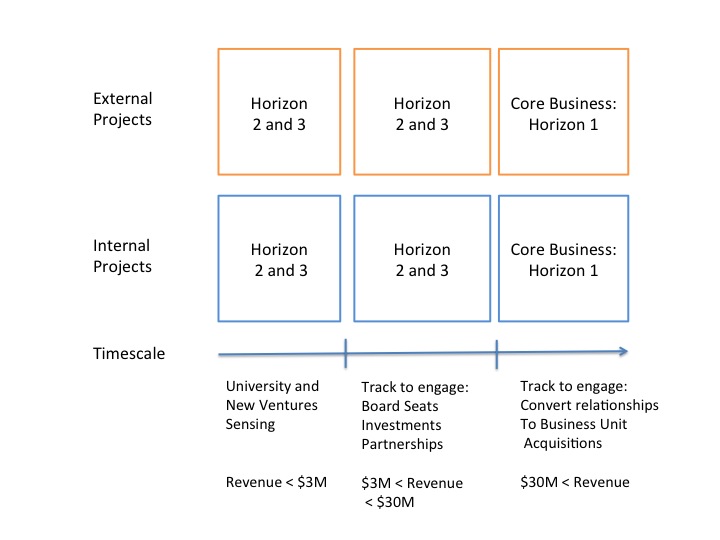

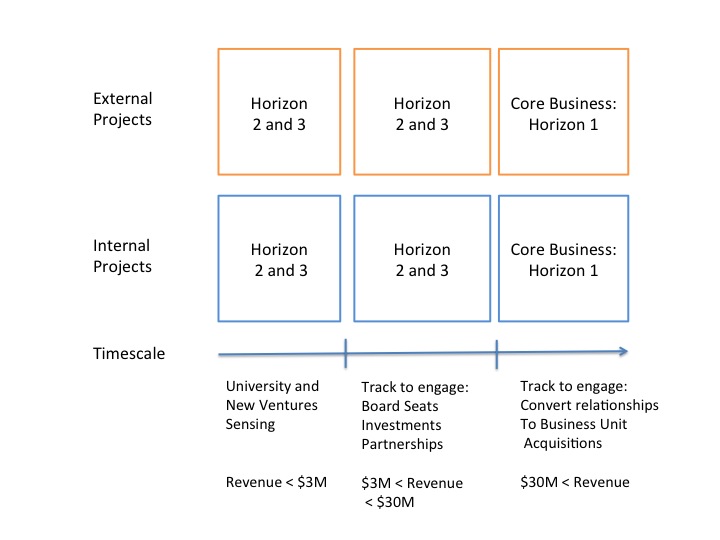

A simple but important point, all of these projects need both communication and relationship management, and not only to be tracked within a list. As projects become more relevant to any given company, the engagement must change from awareness, to board positions and strategic investments, partnerships, supplier agreements, and hopefully acquisitions. These stages must also be managed strategically with an understanding of timing in the relationship as well as strategic understanding of what the new venture can do for the firm.

Over time, some of these projects (external and/or internal) fail and must be removed from the respective portfolio, while others emerge as promising new businesses and become candidates to transition from Horizon 3 and Horizon 2. They are on their way to eventually become the corporation’s next-generation business units in Horizon 1. During this transition, the new businesses should receive additional resources from the corporation and their staff be augmented with individuals, particularly executives, who know how to start scaling businesses.

Is this a new idea? Not completely. Most firms do some variation of this already. Many business unit size acquisitions start out as friendly relationships while the new firm is much younger and the relationship is cultivated over time. The new idea here is that it can be done systematically and strategically within a portfolio instead of as random events.

The Step-by-Step Solution

So what does all this mean for your firm. Here are the simple steps.

- Make a list of your internal projects.

- Make a list of the start-ups you are watching. If you are not watching any, you might want to rethink your approach.

- Unroll the portfolio diagram above. Here is an example

Of course, spreadsheets work pretty well for detailed portfolio tracking. Many firms will do it differently based on their industry types. However, to get started and make this practical, consider column headings such as firm name, stage in portfolio, insights learned per firm, engagement priority, engagement or dis-engagement decision, and of course the changing context and arguments of strategic fit.

In Summary

Large firms and small firm and even university projects are symbiotic, but there are natural barriers that keep them from working together. While this is a larger issue to solve with education and research, for action-oriented firms, the issues are really more about timing, building relationship, and overall portfolio based tracking.

Our position is that it is time to step away from future stories about how the world will change and re-introduce some basic portfolio tracking methods into the innovation process. Of course, it is still crucially important for each firm to know what its future story and strategy will be in order to make sense of its own portfolio. But, the good news is that this problem that is tractable to solve. With an approach to innovation of this type, there will be less reliance on explaining how “deep learning” or “virtual reality” works and more on how the spreadsheet works, and finally your CFO will understand what you are actually talking about.

Viewpoint Highlight:

“From a start-up standpoint, the most common problem I see is potential acquirers – all those big, synergistic companies – not having a clear picture of what’s of strategic value to them. What’s needed is a simple way for these large organizations to map their existing assets, their assets under development, and those small, acquirable companies who provide complementary value to the business.” — Partner, Silicon Valley Venture Fund

“Most acquisitions at Google have had previous relationships develop between people for a long time, even though these firms typically don’t have business relationships with Google during that time. Its seems like they just happen quickly, but actually the relationships have taken time to develop” — Google Executive

Cross-link with Re-Imagining Corporate Innovation with a Silicon Valley Perspective, Evangelos Simoudis