The Sutardja Center is hosting an Imprint Energy Collider on Tuesday, February 23rd at 4 p.m. Imprint Energy is a Cal-founded company that was named one of the top 50 smartest companies of 2015 by the MIT Technology Review (with prestigious company that includes the likes of Google, Amazon, Tesla, and Facebook). Its product is a flexible printed battery that can be printed cheaply on commonly used industrial screen printers. Register here for the kickoff event to learn more about how you can participate. Students in the collider will focus on the power, form factor, and integration requirements of emerging wearable and Internet of Things applications.

Moore’s law states that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit doubles approximately every two years. This biennial doubling of computer processing power has been one of the biggest vehicles of innovation since the observation was noticed by Intel co-founder and former chief executive Gordon Moore in 1965. While Moore’s law works well for computer processors, it does not work for an essential component for most modern electronic devices — the battery. In fact, these little chemical energy packs may be one of the biggest hurdles to creating tech that is more thin, curvy, wearable, and mobile. So, why hasn’t the battery evolved as quickly as other components?

The short answer is that rechargeable lithium-ion batteries require a “lot of packaging,” as stated by Imprint Energy CEO Devin MacKenzie in an interview in 2013. Lithium is highly reactive and can easily catch on fire if not properly sealed in the battery. Thus, lithium batteries are bulky and rigid — which is anathema for electronics designers and engineers looking to create the next big IoT device or wearable.

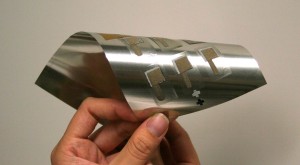

To solve this issue, Imprint Energy has created a battery that uses zinc — a much safer alternative — instead of lithium. “I used to like to tell investors that the main components in our battery are also found in vitamins,” Imprint Energy co-founder Christine Ho said in an interview with KQED, “But then they used to challenge me to eat my battery.” Ditching lithium for zinc has allowed Imprint Energy to create a paper-thin, flexible printed battery without the bulky, rigid packaging. Besides being safer and considerably lighter, these batteries will help engineers and designers experiment with new form factors and shapes for less boxy/more curvy tech possibilities.

Imagine an iPad as thin as a credit card, less bulky smart-watches, a bendable smartphone, or a penny-sized FitBit. The battery may still be behind the evolution of the processor, but ditching lithium for zinc might at least help break through the next barrier in electronic design.